Defending the First Artist In

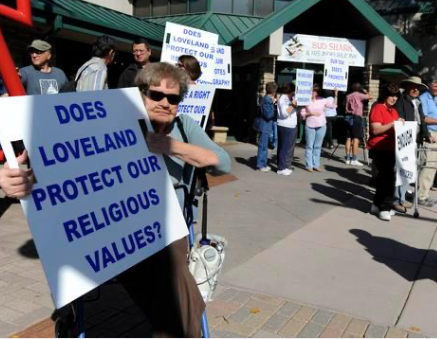

Here’s something I don’t get. Why do people lose their minds over art they don’t personally like or understand? I’m talking, write-letters-angry. Call-your-congressman-angry. Bring-a-crowbar-to-the-exhibit-and-destroy-offending-art-angry?!

Why not just, I don’t know, leave?

Ican’t speak for all curators, but many of us are trying to put shows together that have a reason for being, that do something more than lull people to sleep. We want people to see something new, to consider the world in a fresh way. And, whenever possible, we want people to feel something.

Maybe that’s the real question.

Why do people get so angry when art makes them feel an emotion?

This is nothing new, people getting their undies in a bunch over art, but in this day and age when zealots can arm themselves and destroy works of art (or attack people making that work) because it offends them, it seems like it’s time to talk about…

How to talk about art.

Years ago, while wandering through Dia Beacon, in New York, with a dear friend, we were confronted by Robert Smithson’s Map of Broken Glass (Atlantis). We were silent for a while until my friend leaned over and whispered, “That’s art?”

I’m going to admit a few things here. First, I didn’t connect the sprawling broken glass sculpture to the Robert Smithson of the Spiral Jettyfame, which is also owned and maintained by Dia.

This lack of knowledge brings me to my second admonition: Fear.

Fear of saying something stupid. Fear of sounding pretentious. Fear of not having the facts or correct terminology or even a good reason for defending something.

That day, standing in front of Smithson’s work with my kind and sophisticated friend who really didn’t get it, we had a great conversation about a pile of glass. (I know, a lot of you are dubious, but stay with me on this.)

I, like many of you, do not hold a degree in art history. My understanding is from years of research, conversations with curators and artists, and more than a few boozy evenings with arty friends discussing, arguing, complaining, and defending art.

And so, after 30 years and more than my share of tequila, I present to you a not-art-history-major’s best tips for understanding and enjoying art, whether you like it or not.

One: Understand Where Art Comes From

I don’t make art for the same reason most people don’t make art: I have nothing original to say in paint or print or clay or any other medium. It’s not my calling.

What I know for a fact after years of working with amazing artists is that it’s really hard to be original.

It’s so hard to be original that, when confronted with something stunningly original, we the viewers owe it to the world to stop and pay attention, whether it’s our cup of tea or not.

I’ll go one step further. Putting yourself in front of art, especially when it elicits an emotional reaction, is vital on a personal and societal level. Artists with truly original visions are the ones who speak the truth when others look away.

A lot of times, art (and theatre and music and film, poetry and writing) that makes us feel agitated is also making us see the world differently; it makes us reconsider our beliefs and values.

And those brave souls who created some of the most challenging works of art are people I call the “First Ones In.” These men and women made works of art born out of, as Mary Olivercalled it, “the wild, silky part of ourselves.” The First Ones In did this work knowing the thing they were making would be criticized. In fact, they did it in spite of this awareness.

Two: Maybe your kid could do that BUT he didn’t

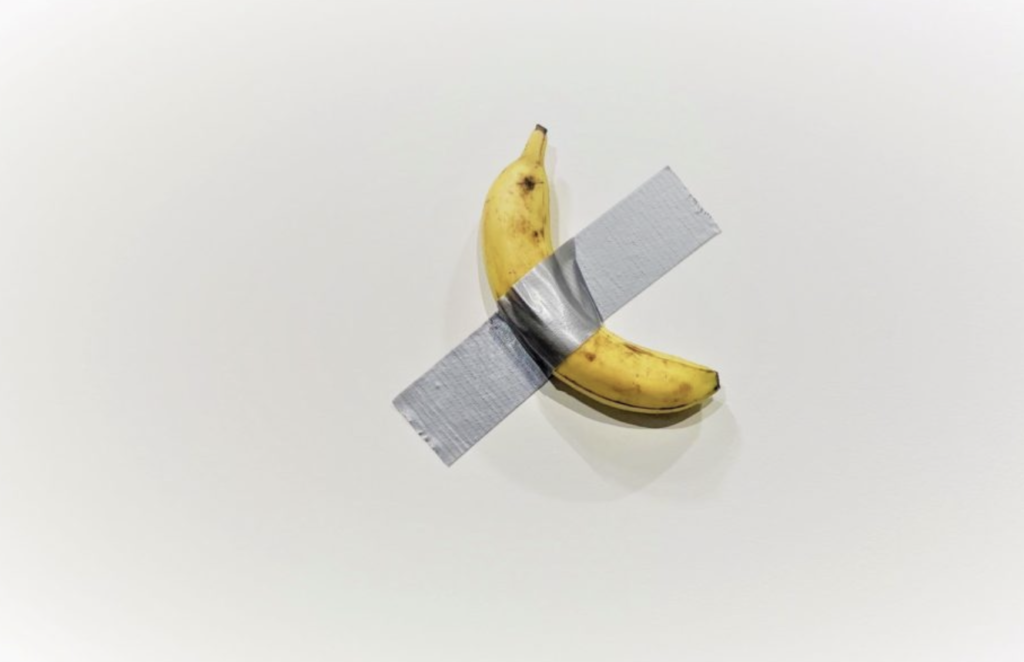

Yes, there’s some crazy stuff out there that’s called “art.” I’m not part of the inner sanctum of museum curators and gallery directors who push forth sharks in glass cylinders or bananas duct-taped to walls, but I do pay attention when I feel uncomfortable, curious, or agitated by a work of art. Something important is happening here and I need to figure out what that is.

NOTE: The banana thing, in my mind, is derivative of Macel Duchamp’s piece, “Fountain.” Duchamp submitted a urinal to be displayed as a sculpture in the first Society of Independent Artists exhibition held in New York, in 1915. Though he was one of the founders of the Society, “Fountain” was rejected from the exhibit, which caused quite an uproar in the artist community because, principally, the Society was formed to create a place where all art could be exhibited and not censored. According to writing on the Tate Modern website, “Fountain” has been seen as the quintessential example of what Duchamp called “readymade” art: an originally manufactured object designated by the artist as a work of art.

Here’s some text about “Fountain” that appeared in a 1917 article called “The Richard Mutt Case,” that was published in the Blind Man and accompanied by a photograph of the original work taken by Alfred Stieglitz:

Mr Mutt’s fountain is not immoral, that is absurd, no more than a bathtub is immoral. It is a fixture that you see every day in plumbers’ shop windows. Whether Mr Mutt with his own hands made the fountain has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.”

In a nutshell…

You would have one hell of a brilliant kid if he or she created work like Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, Joan Mitchell, or Frida Khalo without prior knowledge of these artists’ existence. But your kid didn’t. The kids who made those ground breaking works only existed for a brief, beautiful time; when their lives ended, that work was complete. Everyone who’s made similar work since then is inspired by or simply copying.

This isn’t a bad thing. In fact, so much of what we see in the art world was done by artists who, as Wayne Theibaud put it, stand on the shoulders of giants. In other words, most artists have been trained by someone and have been influenced by many, many others who came before.

In this light, you can consider “Fountain” as the springboard for all kinds of compelling and annoying art like much of what Andy Warhol did by making work that became a running commentary on consumerism.

Bottom line: not all art has aesthetics as its main or only purpose in the world; sometimes it’s a protest, a nudge or a shove into modernity. It is there to make us see our world and the issues we face in a new way.

Three: Make room for the intensity of ambition

In his 2013 critique of an exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York titled, “Inventing Abstraction, 1910-1925: How a Radical Idea Changed Modern Art,“ Peter Schjeldahl wrote about the Wassily Kandinsky painting, “Impression III (Concert)”:

There is something forced, a hysteria of will, about the work, as there is about the drive of Italian Futurists to represent motion, which stumbles on the fact that paintings hold dead still. But the intensity of ambition of the Futurists and Kandinsky batters misgivings.”

Shows like “Inventing Abstraction” illustrate the very best and most important thing art–especially art we don’t understand–can do for us: it let’s us peer into the world of other cultures, times, and lives. We can read history and memorize dates, but isn’t the history of mankind made more alive with color, shape, and texture as attested to by those who possess an “intensity of ambition that batters misgivings?”

In other words, artists are searching for meaning and new forms of expression. Their work doesn’t hinge on whether you like it or not. Your job is to simply let them do their job.

Four: pause

When art makes you react, even negatively, that’s exactly when you need to stop and pay attention. Then start asking questions.

I dropped in an Agnes Marin painting here to talk about taking a breath before dismissing something or getting angry.

White paintings seem to really piss people off. Below is a video that talks about white paintings and adds some very funny clips of people getting all verklempt.

Suffice it to say, white paintings were not created to piss you off; you really didn’t figure into the creation of them. So, take a breath and consider what the painting is doing inside of you.

Some highlights of this video that I love…

“With a white painting, you have to do a lot more work,” said Elisabeth Sherman, assistant curator at the Whitney Museum, NYC. “But it can be a lot more rewarding.”

“White paintings are a fabulous kind of Rorschach test because they offer viewers an ambiguous canvas upon which they can project their own interpretation, emotions, beliefs, and stories onto,” said Dean Peterson, producer of this video.

“It very easy to be dismissive of things we’re not immediately attracted to, so if you have a negative gut reaction of defensiveness or fear or anxiety or rejection, try to move past that to see what’s available afterwards,” explained Sherman and added,

It doesn’t have to change your mind but sometimes moving through the reaction is when you learn the most about the work but also about yourself.”

All this to say that when challenged by conceptual art, ask questions. You don’t have to like it or want to live with it. In fact, whether you like it or not is completely irrelevant when it comes to experiencing art. Consider these experiences as an opportunity to do a little self-reflection.

Five: If you can’t say something nice…

I think disparaging art or anything or anyone you don’t understand is a kind of intolerance that leads us down a slippery slope toward censorship, hate speech and violence. Sorry if that sounds hyperbolic, but you don’t have to look too far into our past to see the ways people have caused tremendous destruction simply over an unwillingness to accept that others have differing opinions or ways of looking at the world.

And really, life is short. Why not let yourself feel your emotions as a way to understand not only art but our collective history?

If you can’t do that, please remember the words of Thumper’s mom–go ahead, say it with me: